Introductory note: This is the second in a two-part series about sexual assault. It examines the health care provider’s role in caring for sexual assault survivors and gives suggestions for how to offer appropriately sensitive health care to that population.

Part 1 addressed where to go and what to do if you’ve been sexually assaulted, and how to be in control of your own health care as a sexual assault survivor. If you haven’t already, please read it before diving into Part 2.

The Day I Relive Over and Over Again…

When I was a young hospital nurse, I remember the day I decided sexual assault survivors need specialized care.

It was a busy shift, and I was triaging a patient. During my initial conversation with her, I mentioned that the doctor would have to do an exam to determine the problem and decide on treatment.

When she asked what exactly the exam entailed, I told her the physician would use a speculum to look at her cervix. Immediately, at the mention of the word speculum, the patient freaked out. I mean, she lost her mind.

I knew why. I needed the patient’s confirmation, though, so I asked, “Do you have a history of sexual assault?”

The answer was yes. Like me, she was a sexual assault survivor. The speculum was her trigger.

I approached the physician and told him the patient could not have a speculum exam. He was also very busy. While there were other methods to gather the information he needed, he knew the quickest way was a speculum exam.

“Would she be more comfortable with a midwife doing the speculum exam?” he asked.

I went back to the patient, and she did prefer a midwife. However, she still refused the speculum exam.

I watched and listened as the midwife tried to convince the patient to agree to the speculum by promising to warm it up with water.

The patient responded with a hesitant, “You can try it.” It was not consent. It was a non-consensual speculum examination with a twist.

I witnessed a full trigger reaction. The patient screamed and cried, violently writhing in the bed. It was battery.

And you know what? The midwife and the doctor didn’t get the information they needed anyway.

I pulled the doctor into the hallway and said, “You realize we just assaulted that girl?”

He didn’t get it and asked me to explain. As we talked, he began to understand sexual assault survivors and their triggers. We ended the conversation in agreement that we needed a better plan for next time.

That day, I failed my patient. And I have never forgotten it.

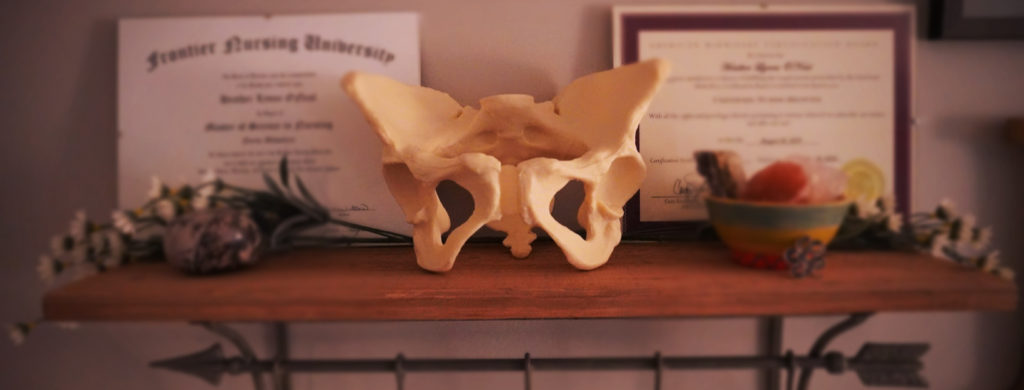

That experience shaped me as a nurse and continues to influence the women’s health care I provide today as a Certified Nurse Midwife with Wise Women Health Care.

In this post, I would like to talk to my fellow health care providers and share nine suggestions for offering sensitive care to sexual assault survivors, no matter where you see patients.

9 Tips for Providing Sensitive Care to Sexual Assault Survivors

-

Acknowledge that sexual assault survivors make up a culture of people.

As health professionals, we often receive sensitivity training on how to provide care to people of different cultures, such as those who identify as gay, bisexual, or transgender. People from all cultures deserve good health care, and those trainings are important.

We can even apply some of those tips and tricks to sexual assault survivors — this culture that we don’t like to admit is a culture.

But acknowledging sexual assault survivors as a culture is truly the first step in providing appropriately sensitive care. This has to happen before any of the following recommendations matter.

-

Recognize your biases and examine your triggers.

This is a tough one, but it’s so important for all providers — male and female. Really stop and think about what biases you have toward sexual assault survivors.

Over the years, I have encountered many male providers, both as a patient and as a nurse. I’ve noticed a tendency not to believe the woman who is describing her sexual assault history.

If you are a male provider, think about if you’ve been the aggressor in a sexual assault situation. For example, perhaps you dated a woman who rejected your advances and you were sure she was overreacting. Or maybe in your marriage relationship, you feel that your wife is not having sex with you enough.

You have to work through your biases to provide sensitive health care to sexual assault providers. Check it and leave it at the door. Your patient gets 15 solid minutes with you and deserves to have your unbiased attention.

Like I said, this bias examination applies to female providers as well. In my case, because I am a sexual assault survivor, I can still become overly emotionally triggered when talking with a patient.

And of course, men can be victims of sexual assault, too.

-

Know that it’s OK to outsource and refer.

I am honored when patients trust me enough to tell me about their sexual assault history. I am all ears, and I want them to talk to me.

However, I am not a therapist. I encourage all my patients who have a history of sexual assault to seek therapy.

As a women’s health care provider, it is OK to say, “Here’s what I can do for you, but we need to outsource the rest.”

This strategy helps you stay professional, while not continuing to trigger the patient.

Providers should know it’s a big responsibility to care for sexual assault survivors. I understand we’re very busy, and we see a lot of different kinds of people. It’s OK to not click with every patient.

This goes back to examining our biases. If you have one, you can tell the patient, “I’m having a bias because of my personal experience, but I want you to get the best care.”

You can recommend a different provider, especially if you know one who specializes in trauma and your patient might have a better experience with that person. Patients will respect that.

Again, you have 15 minutes. Give them what they need that day and set them up for success at their next appointment — even if it’s with a different provider.

-

Update intake forms and screening methods.

The typical patient intake form includes name, date of birth, address, and medical history.

But it’s important to update these forms to make them more culturally appropriate. For example, transgender individuals might like to list the name they prefer, which might not be their given birth name.

The National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC) recognizes that some providers may be hesitant to screen for sexual assault. To overcome these concerns, the NSVRC recommends the following in “Assessing Patients for Sexual Violence: A Guide for Health Care Providers:”

- Normalize sexual assault screening by letting patients know it is part of a routine health history and you pose these questions to all female patients;

- Provide context for the questions by recognizing that sexual violence is common;

- Connect sexual violence to well-being by telling the patient that sexual assault can affect her health; and

- Ask about any unwanted sexual experiences.

In addition to screening patients for sexual assault history, we can be sensitive by noting potential triggers and hard boundaries. A patient can note that she is triggered by having her legs up and does not consent to stirrups. Likewise, if a patient will not consent to a speculum, everyone who interacts with the patient should know not to bring the speculum into the room.

This leads to another important consideration for intake forms and screening: Communication. When you’re gathering medical history, make sure the patient knows what’s going to happen with that information — that it will be in her chart.

If the patient’s chart mentions a history of sexual assault, be sensitive when bringing up that history to the patient, especially when multiple staff members will be interacting with her. How many times does she really need to hear, “I see you have a history of sexual assault”?

The patient does not need to relive her sexual assault every time she goes for a flu shot. Don’t mention it if it doesn’t have a purpose.

If it does have a purpose, like when structuring the patient’s care in a personalized way, flag certain things and make care notes. Document which tests or procedures are an absolute no, a maybe that she’s willing to work on, and a yes that is definitely OK.

When making those notes, though, always remember, consent is a fluid relationship. At any time before or during an appointment, the patient can change her mind and withdraw consent.

-

Set a good example and create a positive culture.

The attitude of a workplace comes from the top and trickles down. Providers often set the tone in an office. Medical assistants, nurses, and administrative staff are watching you.

You and everyone on your team should be comfortable talking to patients about sexual assault. This may require training or continuing education.

To develop and maintain your office culture, have a mission statement and tell people when you hire them, “This is how we feel about sexual assault survivors. If you don’t agree, this is not the job for you.”

In addition, have an environment where if someone starts to stray, you point it out. But also create a culture where people can check you, too.

In a clinic setting, the medical assistant is often the first person to interact with the patient by gathering medical history. The patient’s perception of the office attitude starts with them, so choose staff who will be a part of the culture you want to set.

When a medical assistant tells you that a patient has a history of sexual assault, your response as the provider is critical. If you are rushed or abrasive, your reaction will affect how the staff treats sexual assault survivors.

And if you repeatedly dismiss accounts of sexual assault when the staff discloses this patient information, they will stop telling you. You will be blindsided when the patient mentions it or is triggered by insensitive care. You might even get a bad review as a provider who doesn’t listen.

-

Be open-minded, welcoming, and kind.

This might seem obvious for all health care providers, no matter who the patient is.

But when caring for sexual assault survivors, there are some things you can do to make the patient feel more comfortable.

- Create a welcoming physical environment. Ditch fluorescent lighting if you can, so the space feels less like a place to have surgery and more like a personal experience. Make sure the office is clean. Consider adding plants or wall art.

- Allow patients to communicate in the way that suits them best, whether that’s verbally or in writing — electronically or on paper. For example, if a patient doesn’t want to talk about her sexual assault history but hands you a letter, accept it and read it carefully.

- Welcome support persons who accompany the patient.

- Exhibit a calm attitude.Sexual assault survivors often are fearful and do not want to be frightened.

- Be empathetic and do not judgewhen your patient describes her experiences.

- Validate the patient’s experienceby saying something like, “It took a lot of courage to tell me this” or “You didn’t do anything to deserve this.” For more information on how to talk to sexual assault providers, read these suggestions from the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network.

- Allow patients to ask questionsand answer them patiently and honestly. Really listen to the patient’s triggers and accommodate as necessary.

- Let patients be comfortable.Maybe she prefers to wear her socks or leave her skirt on for the exam.

-

Schedule appropriately.

I’ve worked in clinics and hospitals. I get it — I know how busy it is.

But one of the most important things you can give a sexual assault survivor is time. Please don’t be in a hurry.

If a patient tells the scheduler she has something she needs to discuss and that it will require a longer appointment, honor that request.

There will be times when a medical assistant or nurse learns about the patient’s sexual assault history at the start of the appointment. In this case, if you have patients in two exam rooms, you can pop in to the first patient’s room and let her know that you’d like to spend more time with her, so you’re going to see the other patient first.

For returning patients who have already disclosed a history of sexual assault, plan to see those patients right before a lunch break or at the end of the day. This allows you more time to help the patient feel comfortable before an exam.

-

Offer less invasive care whenever possible.

I alluded to this above in the section about triggers, but I want to explain in more detail how we can accommodate sexual assault survivors by offering alternatives to the standard well-woman exams.

- Breast exam.If a patient has had her breast groped and is triggered by a breast exam, teach her how to do the breast exam herself and have her tell you what she feels. Often, breast exams are imperfect at best anyway.

- Speculum exam. Warm up the speculum. A cold speculum can cause vaginal spasms, and the vagina will not open. You can also consider using a pediatric speculum.

- Pap smear.Use lubrication. Some pathologists feel it interferes with the sample, but I’ve not had one result come back with insufficient cells. We don’t want to make anyone sore or uncomfortable, and lubrication helps.

- Bimanual exam. This is such an uncomfortable and invasive exam, especially for sexual assault survivors. Ask yourself if it’s really needed. This exam is not always effective and can lead to unnecessary biopsies and ultrasounds. If there isn’t a specific reason to perform this exam, it is perfectly fine to leave it out. Nothing definitive comes from that exam anyway.

- Consider letting patients swab themselves. For example, research shows that patients can do a Group B Strep swab just as well as a provider. Most patients, if given the option, will swab themselves. It gives them much more body autonomy and sets up a relationship of trust between the provider and the patient.

No matter what exam or procedure you are performing, always explain to the patient what you’re doing before you do it and ask for consent!

-

Provide resources.

When talking with a sexual assault survivor about her care, you may identify tests that can wait for a future appointment. For example, a pap smear is never an emergency; if you need to wait a month, it’s going to be fine.

Discuss the plan for the next appointment and have materials available for the patient, so she can prepare mentally.

If she prefers hard copies, offer handouts. If she would rather read a digital version, email her resources. Use the method that is easiest for the patient to learn.

How Wise Women Health Care is sensitive to sexual assault survivors

At Wise Women Health Care, I work with patients to tailor their care in a non-triggering way. I strive to implement the suggestions I’ve mentioned in this post.

Patients can choose to receive care in their own homes, and I also offer care in my home. The latter can be a great option for sexual assault survivors who have experienced unwanted sexual experiences in their home. Learn more about my services here. For an appointment, contact me here or text 304-449-6670 for an appointment.

If you are a fellow women’s health professional and would like to refer a patient to me or you just want to talk about this topic, please contact me here or at 304-449-6670.

Resources

Assessing Patients for Sexual Violence: A Guide for Health Care Providers— National Sexual Violence Resource Center

Tips for Talking with Survivors of Sexual Assault– Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN)

Discussing sexual assault/abuse and intimate partner violence— RISE

Caring for survivors of sexual violence: A guide for primary care NPs— Women’s Healthcare: A Clinical Journal for NPs

Guidelines for medico-legal care for victims of sexual violence— World Health Organization